Introduction

Today, we explore one of the most significant Buddhist sites in Uzbekistan—Fayaz Tepe. Located along the Silk Road, Uzbekistan’s capital is Tashkent. Originally, the people followed Zoroastrianism (fire worship), but later, Buddhism gained limited influence in the region.

Historical Accounts: Xuanzang’s Journey (630 CE / 1173 BE)

When the Chinese monk Xuanzang (Tang Sanzang) passed through Samarkand, he recorded:

"The king and people did not initially believe in the Buddha’s teachings, adhering instead to fire worship (Zoroastrianism). There were two monasteries in the city, but no resident monks. If foreign monks tried to stay, locals would light fires to drive them away. When I arrived, the king received me reluctantly, but after hearing the Dharma, he converted and took precepts. Two novice monks accompanying me visited the monasteries but were chased away with fire. The enraged king wanted to cut off the attackers’ hands, but I intervened, and they were merely exiled. Later, I organized a Dharma assembly, and many people embraced Buddhism."

(Keng Lian Sibunruang, The Biography of Xuanzang, p. 88)

Key Takeaway:

Buddhism struggled against Zoroastrian dominance until Xuanzang’s mission.

By 1057 CE (1600 BE), Muslim conquests erased most Buddhist presence.

Archaeological Rediscovery

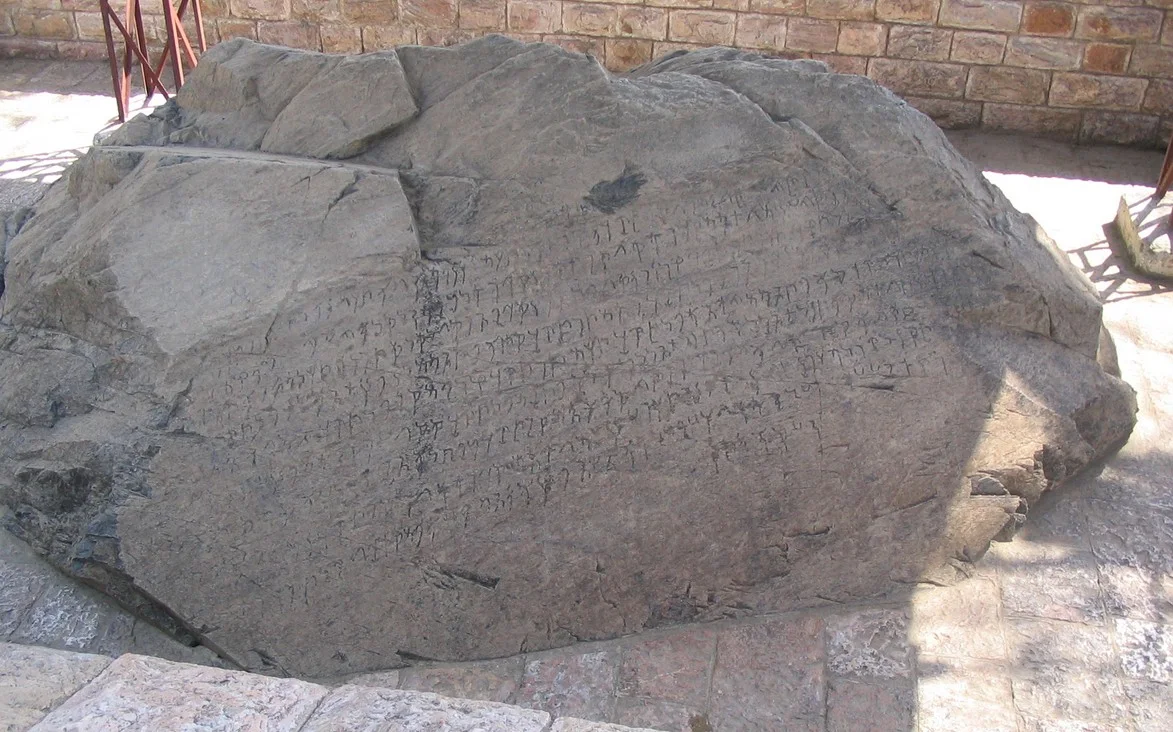

In 1960 CE (2503 BE), Russian archaeologist V.A. Kuznetsov excavated Fayaz Tepe, uncovering:

A Buddhist monastery with Gandharan-style artifacts, including a seated Buddha preaching.

Now displayed at the National Museum of Tashkent.

Recent Research:

Thai scholar Prof. Dr. Banjob Bannaruji and team visited Uzbekistan, confirming ~20 Buddhist sites, with four major ones excavated:

Fayaz Tepe

Kara Tepe

Ayrtam

Zurmala

Modern Context

Population: 30 million (94% Muslim).

Capital: Tashkent.

Legacy: Uzbekistan’s Buddhist ruins reflect its Silk Road role as a crossroads of faiths.

Significance:

Proof of Buddhism’s fleeting but profound impact in Central Asia.

Artifacts show Gandharan influence, linking Uzbekistan to Afghanistan/Pakistan’s Buddhist art.

Why This Matters

Cultural Exchange: Uzbekistan’s Buddhist past highlights Silk Road diversity.

Preservation Challenge: Many sites remain unexcavated, risking loss to time.

(Note: "Fayaz Tepe" is sometimes spelled "Fayoz-Tepe" or "Fayaztepa.")

.jpeg)

.jpeg)