Let us pay homage to the Five Infinities with joined palms, bowing with humility: Namo Buddhassa. Namo Dhammassa. Namo Sanghassa. Namo Matapitussa. Namo Acariyassa.

ဝန္ဒာမိ

ဝန္ဒာမိ စေတိယံ သဗ္ဗံ၊ သဗ္ဗဋ္ဌာနေသု ပတိဋ္ဌိတံ။ ယေ စ ဒန္တာ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ ဒန္တာ အနာဂတာ၊

ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ ဒန္တာ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိ တေ အဟံ။

vandāmi cetiyaṃ sabbaṃ, sabbaṭṭhānesu patiṭṭhitaṃ. Ye ca dantā atītā ca, ye ca dantā anāgatā, paccuppannā ca ye dantā, sabbe vandāmi te ahaṃ.

Monastic Dhamma Vinaya Curriculum for Monks ( Assessment book )

💻 Available Now on Amazon Kindle!

📖 Assessment book for the 227 rules of pātimokkha: Monastic Dhamma Vinaya Curriculum for Monks

By Bhikkhu Indasoma Siridantamahāpālaka

Now Available on Kindle!

Click below to embark on a journey through time and wisdom.

Purchase this on Amazon, or download it for free from my Academia.edu page:https://bhikkhuindasomasiridantamahapalaka.academia.edu/

Preserve the past. Embrace the present.

🔗 Your Copy Today!

Preserve the past. Embrace the present. Inspire the future.

Book sale proceeds will fund advanced DNA and carbon-14 dating, and relic preservation.

Law of Dependent Origination (The Paticcasmuppada)

💻 Available Now on Amazon Kindle!

📖 Paticcasamuppada (Law of Dependent Origination)

By Bhikkhu Indasoma Siridantamahāpālaka

Now Available on Kindle!

Click below to embark on a journey through time and wisdom.

🔗 Get Your Copy Today!

Preserve the past. Embrace the present. Inspire the future.

Book sale proceeds will fund advanced DNA and carbon-14 dating, and relic preservation.

✨ Discover the Legacy of Sacred Treasures ✨

Book sale proceeds will fund advanced DNA and carbon-14 dating, and relic preservation.

💻 Available Now on Amazon Kindle!

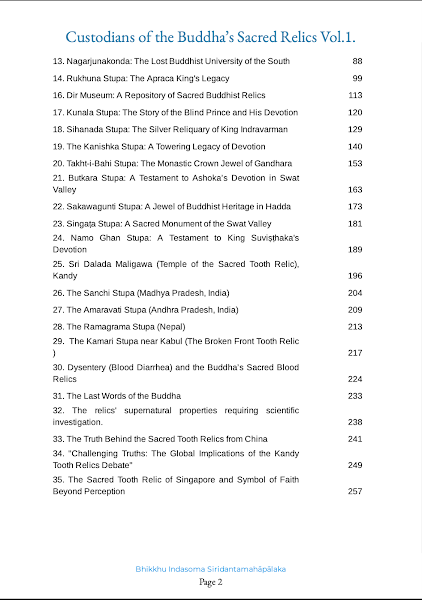

📖 Custodians of the Buddha’s Sacred Relics, Vol. 1

By Bhikkhu Indasoma Siridantamahāpālaka

Now Available on Kindle!

Preserve the past. Embrace the present. Inspire the future.

The Profound Experience of Professor Dr. Yin Yin Than

Professor Dr. Yin Yin Than, esteemed head of the Faculty of Myanmar Language at the University of Foreign Languages in Yangon, has shared a remarkable experience that underscores the profound significance of Buddha relics in Buddhist practice. One serene evening, while engaged in personal worship within her home’s designated worship room, she encountered an extraordinary phenomenon that would deeply impact her spiritual journey.

During her worship, Professor Than was suddenly captivated by a sound reminiscent of countless bees buzzing. Intrigued yet bewildered, she turned her attention towards the sacred Buddha Shining Place in her home. To her astonishment, she witnessed cascading relics descending from the canopy above—an ethereal sight that evoked a sense of joy and divine presence. This moment of serendipity filled her heart with happiness and awe, leading her to collect the fallen relics with reverence.

This experience not only enriched Professor Than’s personal worship routine but also reinforced her belief in the sacredness and transformative power of relics associated with the Buddha. She made it a daily practice to honor the relics, integrating them as focal points in her spiritual routine. The relics serve as tangible reminders of the Buddha’s teachings and life, embodying a connection to something far greater than oneself.

Having had the unique opportunity to interview Professor Dr. Yin Yin Than, it became evident that her profound encounter is more than just an extraordinary tale; it is a narrative steeped in devotion and reverence. Her experience highlights the intersection between the material and spiritual realms, illustrating how moments of divine revelation can profoundly shape one’s faith. The presence of the relics not only enhanced her personal worship but also reinforced the significance of mindfulness and devotion in the pursuit of enlightenment.

Professor Dr. Yin Yin Than's encounter with the Buddha relics serves as a compelling testament to the enduring spiritual journey that Buddhism encompasses. It is an affirmation of faith, illustrating how sacred experiences can transcend the ordinary, fostering a deeper connection to the teachings of the Buddha. Such narratives remind us of the transformative power of spiritual practice and the continued relevance of relics in contemporary belief systems.

From Six Years to Two Minutes

"At the beginning of the Dhamma, there must be spiritual urgency (saṃvega). When one has never heard something before, #wisdom_of_spiritual_urgency makes it easier to understand the Dhamma. However, having the wrong teacher won't help. #One_must_have_the_right_teacher.

In ancient times, there were two wealthy young men, Upatissa and Kolita. They were merchants. In worldly knowledge, they were unmatched. No one could surpass them in any field. They were accomplished in every way. Upatissa would later become Venerable Sāriputta, foremost in wisdom, and Kolita would become Venerable Moggallāna.

They conducted trade between villages, cities, and countries. That year, there was a hilltop festival performance scheduled for the full moon day of Tazaungmon (November). They returned just in time for this festival. They arrived in the city slightly late, so they rested at home briefly and had their meal before heading to the festival pavilion. It's said there were over forty thousand spectators at this hilltop festival performance.

This was the season and festival when young men and women would enjoy themselves in the human realm. When these two wealthy young men arrived at the festival pavilion, they didn't need to ask for seats - people made way for them as soon as they saw them. When the performance reached its peak, shouldn't they look in all eight directions? When they looked in all four cardinal directions, didn't the surrounding spectators say that the two wealthy young men were looking for their sweethearts? In common language they would say 'sweetheart,' but in performance terminology, they used the word 'myar' (beloved). At festivals like this, this was the common entertainment."

This is the beginning of a famous story that leads to these two friends' spiritual awakening and eventual attainment of arahatship as the Buddha's chief disciples. The narrative emphasizes how even those who were accomplished in worldly matters could be moved to seek deeper spiritual truth through saṃvega (spiritual urgency).

In ancient times, there were two wealthy young men, Upatissa and Kolita. They were merchants. In worldly knowledge, they were unmatched. No one could surpass them in any field. They were accomplished in every way. Upatissa would later become Venerable Sāriputta, foremost in wisdom, and Kolita would become Venerable Moggallāna.

They conducted trade between villages, cities, and countries. That year, there was a hilltop festival performance scheduled for the full moon day of Tazaungmon (November). They returned just in time for this festival. They arrived in the city slightly late, so they rested at home briefly and had their meal before heading to the festival pavilion. It's said there were over forty thousand spectators at this hilltop festival performance.

This was the season and festival when young men and women would enjoy themselves in the human realm. When these two wealthy young men arrived at the festival pavilion, they didn't need to ask for seats - people made way for them as soon as they saw them. When the performance reached its peak, shouldn't they look in all eight directions? When they looked in all four cardinal directions, didn't the surrounding spectators say that the two wealthy young men were looking for their sweethearts? In common language they would say 'sweetheart,' but in performance terminology, they used the word 'myar' (beloved). At festivals like this, this was the common entertainment."

This is the beginning of a famous story that leads to these two friends' spiritual awakening and eventual attainment of arahatship as the Buddha's chief disciples. The narrative emphasizes how even those who were accomplished in worldly matters could be moved to seek deeper spiritual truth through saṃvega (spiritual urgency).

"After looking in all directions, the two wealthy young men reflected: 'Friend, there are over forty thousand people here. The human lifespan is about one hundred years. How old are we?' They were in their twenties, young men in their prime. 'Among these forty thousand people, they're all bound to die within a hundred years. We're in our twenties, so we have about 80 years left. Those who are eighty have twenty years left, those who are ninety have one year, and those who are ninety-nine years and eleven months have just one month left. Shouldn't we calculate death this way?'

'Friend, I think where there is aging, there must be a state of non-aging. Where there is sickness, there must be a state without sickness. Where there is death, there must be a state of deathlessness. Do you believe this?' 'Yes, I believe.'

'What is our current occupation?' 'We're merchants. We trade for our livelihood.' 'Then shall we die seeking material wealth, or shall we die seeking the Dhamma?' This was Upatissa asking. Kolita replied, '#We_shall_die_seeking_the_Dhamma.' 'We won't die just seeking material wealth.'

If you asked people today, most would probably die seeking material wealth, few would die seeking Dhamma. Isn't this worth considering? They decided not to watch the performance and returned home. While the crowd thought they were looking for sweethearts, they were actually contemplating with spiritual urgency (saṃvega). That night, they asked their parents' permission and left with just small travel bags.

After traveling for 2-3 days, they met Venerable Sañjaya on a forest path. He was walking meditation in his monastery compound. Upatissa and Kolita approached and paid respects, as is Buddhist custom when meeting ascetics. The teacher asked, 'Young men, where are you going?' They replied, 'We're searching for the teaching of non-aging, non-sickness, and deathlessness.'

He pointed them to the monastery, saying 'Look at those people - I'm teaching that very Dhamma.' Overjoyed, they requested, 'Venerable sir, from today please guide us toward the good and away from evil, like your own disciples.' They studied there, but after one month, one year, even six years, they hadn't found what they were seeking. 'Perhaps our wisdom is dull,' they thought.

They discussed with other meditation practitioners but found they knew no more than themselves. They discussed with monks but found the same. After many such discussions, they realized #their_teacher_himself_didn't_truly_know_the_Dhamma. They contemplated this carefully. They took their leave and departed from the monastery. About three miles away, they came to a fork in the road. 'We've spent so much time together...'"

This part of the narrative shows their spiritual urgency (saṃvega) and their sincere search for liberation, which would eventually lead them to the Buddha and their becoming his chief disciples.

'Friend, I think where there is aging, there must be a state of non-aging. Where there is sickness, there must be a state without sickness. Where there is death, there must be a state of deathlessness. Do you believe this?' 'Yes, I believe.'

'What is our current occupation?' 'We're merchants. We trade for our livelihood.' 'Then shall we die seeking material wealth, or shall we die seeking the Dhamma?' This was Upatissa asking. Kolita replied, '#We_shall_die_seeking_the_Dhamma.' 'We won't die just seeking material wealth.'

If you asked people today, most would probably die seeking material wealth, few would die seeking Dhamma. Isn't this worth considering? They decided not to watch the performance and returned home. While the crowd thought they were looking for sweethearts, they were actually contemplating with spiritual urgency (saṃvega). That night, they asked their parents' permission and left with just small travel bags.

After traveling for 2-3 days, they met Venerable Sañjaya on a forest path. He was walking meditation in his monastery compound. Upatissa and Kolita approached and paid respects, as is Buddhist custom when meeting ascetics. The teacher asked, 'Young men, where are you going?' They replied, 'We're searching for the teaching of non-aging, non-sickness, and deathlessness.'

He pointed them to the monastery, saying 'Look at those people - I'm teaching that very Dhamma.' Overjoyed, they requested, 'Venerable sir, from today please guide us toward the good and away from evil, like your own disciples.' They studied there, but after one month, one year, even six years, they hadn't found what they were seeking. 'Perhaps our wisdom is dull,' they thought.

They discussed with other meditation practitioners but found they knew no more than themselves. They discussed with monks but found the same. After many such discussions, they realized #their_teacher_himself_didn't_truly_know_the_Dhamma. They contemplated this carefully. They took their leave and departed from the monastery. About three miles away, they came to a fork in the road. 'We've spent so much time together...'"

This part of the narrative shows their spiritual urgency (saṃvega) and their sincere search for liberation, which would eventually lead them to the Buddha and their becoming his chief disciples.

"'You take the left path, I'll take the right. When you find the supreme Dhamma, teach it to me. If I find it, I'll teach you.' Didn't they make this promise? Then they parted ways. [The narrator comments] I (as a monk) couldn't bear such separation - I'd be afraid. But they weren't afraid. #Their_desire_to_know_the_Dhamma_was_so_strong. My fear comes from being weak in Dhamma practice, focusing on fearful things.

Near Rajagaha, it was Venerable Assaji's turn for alms round (one of the five ascetics - Kondañña, Vappa, Bhaddiya, Mahanama, and Assaji). One monk's alms round would feed six, including the Buddha. They maintained their practice of teaching, listening to Dhamma, and alms rounds without fail. When Upatissa saw Venerable Assaji's deportment, he thought, 'This person is extraordinary. I've never seen a monk with such perfect composure.' He considered whether to approach him.

He thought, 'If I question him now during his alms round, it might delay him and cause problems.' So he followed Assaji discretely, maintaining a distance of about forty yards in the city. When they were two furlongs outside the city after the alms round, he approached saying, 'Please wait, Venerable Sir. From the moment I saw your deportment, I wanted to ask questions but didn't want to interfere with your alms round. Now that you've completed your meal, I believe you possess the Dhamma I seek.'

'What kind of teachings have you studied?' he asked. 'I've studied about aggregates, sense bases, elements, and noble truths.' 'Who is your teacher?' 'The Buddha Gotama.' Now he had found a genuine Buddha! 'Please teach me the Dhamma,' he requested. Assaji replied, 'I've only completed my monastic duties seven days ago. I cannot teach extensively, though I have completed my task [of enlightenment].'

'Venerable Sir, I don't need elaborate grammar or syntax. If I can understand just one meaning, whether you teach it briefly or extensively...' He meant he needed to truly understand just one point. Then Venerable Assaji taught:

'Ye dhammā hetuppabhavā, tesaṃ hetuṃ tathāgato āha, tesañca yo nirodho, evaṃvādī mahāsamaṇo...'

Before Assaji could finish the verse, Upatissa said, 'Stop, stop, Venerable Sir, you'll tire yourself. I understand it all!' The verse wasn't even finished. In just two minutes, he attained stream-entry (sotāpanna)."

Near Rajagaha, it was Venerable Assaji's turn for alms round (one of the five ascetics - Kondañña, Vappa, Bhaddiya, Mahanama, and Assaji). One monk's alms round would feed six, including the Buddha. They maintained their practice of teaching, listening to Dhamma, and alms rounds without fail. When Upatissa saw Venerable Assaji's deportment, he thought, 'This person is extraordinary. I've never seen a monk with such perfect composure.' He considered whether to approach him.

He thought, 'If I question him now during his alms round, it might delay him and cause problems.' So he followed Assaji discretely, maintaining a distance of about forty yards in the city. When they were two furlongs outside the city after the alms round, he approached saying, 'Please wait, Venerable Sir. From the moment I saw your deportment, I wanted to ask questions but didn't want to interfere with your alms round. Now that you've completed your meal, I believe you possess the Dhamma I seek.'

'What kind of teachings have you studied?' he asked. 'I've studied about aggregates, sense bases, elements, and noble truths.' 'Who is your teacher?' 'The Buddha Gotama.' Now he had found a genuine Buddha! 'Please teach me the Dhamma,' he requested. Assaji replied, 'I've only completed my monastic duties seven days ago. I cannot teach extensively, though I have completed my task [of enlightenment].'

'Venerable Sir, I don't need elaborate grammar or syntax. If I can understand just one meaning, whether you teach it briefly or extensively...' He meant he needed to truly understand just one point. Then Venerable Assaji taught:

'Ye dhammā hetuppabhavā, tesaṃ hetuṃ tathāgato āha, tesañca yo nirodho, evaṃvādī mahāsamaṇo...'

Before Assaji could finish the verse, Upatissa said, 'Stop, stop, Venerable Sir, you'll tire yourself. I understand it all!' The verse wasn't even finished. In just two minutes, he attained stream-entry (sotāpanna)."

"Now, after one year, nothing happened. After three years, still nothing. But there, it took just two minutes! With Sañjaya, they spent six years without attaining even one path and fruit. #When_the_teacher_is_wrong_there_are_no_results. With Venerable Assaji, the true Dhamma led to stream-entry in two minutes. The teacher was left amazed when the student said 'I understand it all!'

'Ye dhammā' means: Whatever phenomena (five aggregates, mind-matter) that arise from causes, the Buddha teaches those causes and their cessation.

Looking at this, aren't there four sections of Dependent Origination? Two sections for seeing, two for hearing, two for touching. These two sections include consciousness, name-and-form, six sense bases, contact, and feeling. #Is_it_happening_by_itself_or_due_to_causes? Looking for causes, don't we find ignorance and formations?

Isn't it important to examine what ignorance misconceives? Doesn't it misconceive the aggregates as being persons and beings? What's really there to be seen - beings or the five aggregates? These aggregates are signless (animitta), impermanent. #It_appears_as_mere_phenomena.

Can there be shape in the signless? How clear this is! Misconceiving this as persons and beings is ignorance. Doesn't ignorance lead to craving? Doesn't craving lead to clinging? When we categorize ignorance, craving, and clinging, which Noble Truth is it? (The Noble Truth of Origin)

That Origin causes suffering. Therefore, Path and Cessation - #One_must_be_dispassionate_to_become_a_Buddha. Doesn't he teach that Origin causes suffering? Have you heard that one must be dispassionate to become a Buddha?

When consciousness-aggregate 'knows,' doesn't it cease? Think about it. When we see consciousness-aggregate, do we see beings? What we see - is it beings or consciousness-aggregate?

Doesn't it have mental phenomena? Think - are they beings or mental phenomena? Are the changing things beings or physical phenomena? #These_are_just_mind_and_matter. Don't they arise and cease? Isn't this taught as arising and passing? Which Noble Truth is this? (The Noble Truth of Suffering)

When one knows it as the Truth of Suffering, does craving still arise? 'Knowing!' Why doesn't craving arise? Isn't it worth examining? When the root is cut, doesn't the top wither? Isn't ignorance the root? Isn't it part of the cycle from ignorance to aging and death? #When_ignorance_ceases, does craving still come? Does clinging come? Does kamma come? Don't the three types of Dependent Origination cease? Doesn't the cycle of aggregates end? #Isn't_this_called_Cessation? Strive to reach this point. Isn't this worth emulating? These are the essential points. We study to understand these aggregates.

Present moment aggregates arising-ceasing

What Truth is this? (Truth of Suffering)

The knowing is (Truth of Path)

Craving is (Truth of Origin)

No more aggregates arising is (Truth of Cessation)

How many sections in Dependent Origination? (Four sections)

How many factors in each section? (Five factors)

Five times four equals (Twenty)

These eight aspects (Should be easily memorized as the way to liberation)

Sadhu! Together let us keep the Dharma wheel rolling."

'Ye dhammā' means: Whatever phenomena (five aggregates, mind-matter) that arise from causes, the Buddha teaches those causes and their cessation.

Looking at this, aren't there four sections of Dependent Origination? Two sections for seeing, two for hearing, two for touching. These two sections include consciousness, name-and-form, six sense bases, contact, and feeling. #Is_it_happening_by_itself_or_due_to_causes? Looking for causes, don't we find ignorance and formations?

Isn't it important to examine what ignorance misconceives? Doesn't it misconceive the aggregates as being persons and beings? What's really there to be seen - beings or the five aggregates? These aggregates are signless (animitta), impermanent. #It_appears_as_mere_phenomena.

Can there be shape in the signless? How clear this is! Misconceiving this as persons and beings is ignorance. Doesn't ignorance lead to craving? Doesn't craving lead to clinging? When we categorize ignorance, craving, and clinging, which Noble Truth is it? (The Noble Truth of Origin)

That Origin causes suffering. Therefore, Path and Cessation - #One_must_be_dispassionate_to_become_a_Buddha. Doesn't he teach that Origin causes suffering? Have you heard that one must be dispassionate to become a Buddha?

When consciousness-aggregate 'knows,' doesn't it cease? Think about it. When we see consciousness-aggregate, do we see beings? What we see - is it beings or consciousness-aggregate?

Doesn't it have mental phenomena? Think - are they beings or mental phenomena? Are the changing things beings or physical phenomena? #These_are_just_mind_and_matter. Don't they arise and cease? Isn't this taught as arising and passing? Which Noble Truth is this? (The Noble Truth of Suffering)

When one knows it as the Truth of Suffering, does craving still arise? 'Knowing!' Why doesn't craving arise? Isn't it worth examining? When the root is cut, doesn't the top wither? Isn't ignorance the root? Isn't it part of the cycle from ignorance to aging and death? #When_ignorance_ceases, does craving still come? Does clinging come? Does kamma come? Don't the three types of Dependent Origination cease? Doesn't the cycle of aggregates end? #Isn't_this_called_Cessation? Strive to reach this point. Isn't this worth emulating? These are the essential points. We study to understand these aggregates.

Present moment aggregates arising-ceasing

What Truth is this? (Truth of Suffering)

The knowing is (Truth of Path)

Craving is (Truth of Origin)

No more aggregates arising is (Truth of Cessation)

How many sections in Dependent Origination? (Four sections)

How many factors in each section? (Five factors)

Five times four equals (Twenty)

These eight aspects (Should be easily memorized as the way to liberation)

Sadhu! Together let us keep the Dharma wheel rolling."

Breaking the Chain of Anger (Kodhassa Samucchedana)

"According to conventional truth and right view of ownership of kamma (kammassakatā sammādiṭṭhi), aren't we taught to believe in two types of kamma - wholesome and unwholesome?

From killing to taking intoxicants, from killing to wrong views - when committed, are these wholesome or unwholesome? Due to unwholesome kamma, don't the results lead to hell realms, animal realm, peta realm, and asura realm after death? Is this happiness or suffering? This comes from unwholesome kamma. Isn't it frightening?

When one abstains from killing through to abstaining from intoxicants, from killing through to wrong views - is this unwholesome or wholesome? Don't the results of wholesome kamma lead to human realm and six deva realms? Is this suffering or happiness? This is why we must believe in kamma and its results.

Would someone who truly believes in kamma still consult fortune tellers, spirit mediums, or occultists? Would someone who believes in kamma create new unwholesome kamma? When someone creates new unwholesome kamma, is it because they believe in kamma or don't believe? This needs careful examination. Therefore, understanding kamma and its results is essential.

In the story of Sunluntha Thera, there are people whose wholesome kamma is ripening and those whose unwholesome kamma is ripening. Those experiencing wholesome kamma results are smiling, while those experiencing unwholesome kamma results are frowning. This is the difference between wholesome and unwholesome kamma. Unwholesome leads to suffering, wholesome leads to happiness. People can talk about it, but not understanding the true meaning is the problem.

Ask anyone - do they want to suffer or be happy? They'll say they want happiness. If you want happiness, you must do actions that lead to happiness. If you want happiness but do actions that lead to suffering, how can you expect happiness?

This is why belief in kamma is necessary. Everyone says they want happiness, but their actions lead to suffering. They want happiness but perform actions leading to suffering."

From killing to taking intoxicants, from killing to wrong views - when committed, are these wholesome or unwholesome? Due to unwholesome kamma, don't the results lead to hell realms, animal realm, peta realm, and asura realm after death? Is this happiness or suffering? This comes from unwholesome kamma. Isn't it frightening?

When one abstains from killing through to abstaining from intoxicants, from killing through to wrong views - is this unwholesome or wholesome? Don't the results of wholesome kamma lead to human realm and six deva realms? Is this suffering or happiness? This is why we must believe in kamma and its results.

Would someone who truly believes in kamma still consult fortune tellers, spirit mediums, or occultists? Would someone who believes in kamma create new unwholesome kamma? When someone creates new unwholesome kamma, is it because they believe in kamma or don't believe? This needs careful examination. Therefore, understanding kamma and its results is essential.

In the story of Sunluntha Thera, there are people whose wholesome kamma is ripening and those whose unwholesome kamma is ripening. Those experiencing wholesome kamma results are smiling, while those experiencing unwholesome kamma results are frowning. This is the difference between wholesome and unwholesome kamma. Unwholesome leads to suffering, wholesome leads to happiness. People can talk about it, but not understanding the true meaning is the problem.

Ask anyone - do they want to suffer or be happy? They'll say they want happiness. If you want happiness, you must do actions that lead to happiness. If you want happiness but do actions that lead to suffering, how can you expect happiness?

This is why belief in kamma is necessary. Everyone says they want happiness, but their actions lead to suffering. They want happiness but perform actions leading to suffering."

"If someone speaks ill of you in public, humiliating you, would you get angry? Is this anger wholesome or unwholesome? You want happiness, but anger is unwholesome.

You say you want happiness but perform unwholesome actions. Didn't the Buddha teach that anger is unwholesome? This already leads to suffering. Therefore, we need to avoid anger.

From the conventional truth perspective, when someone insults you, does your skin peel off? There's no need for anger. If your skin was peeling, then you should be angry. If there's no physical harm, is there any need for anger? Does it hurt like a needle prick?

In the Mangala Sutta, isn't patience declared supreme? We must examine the benefits and drawbacks. When we know there's no physical harm and no real pain, we can practice patience. Doesn't this resolve things on the conventional level?

From the ultimate truth perspective, aren't we taught to be mindful when hearing? When being mindful, is it a person or just sound? When someone calls you 'dog' or 'thief' - with mindfulness, is it a person or just sound?

Doesn't the sound itself provide evidence? Do you see a person or hear a sound? With the ear, you only experience sound. Is there any 'thief' to be found in the sound? Is there anything in the mere sound to be angry about?

Consider this: If a foreigner who doesn't understand Burmese is insulted in Burmese, would they get angry? They hear the sound, but is there anything inherently anger-provoking in the sound? If anger was inherent in the sound itself, wouldn't they become angry immediately upon hearing it?

After a year, when they understand Burmese, they might ask what 'dog's son' means. When it's explained, then they become angry. Did they get angry before understanding? This shows that anger comes from wrong attention (ayoniso manasikāra) and wrong perception.

In the form aggregate of sound, isn't it wrong perception to take it as an insult? When examined, is it an insult or just sound? The Buddha taught that hearing is covered by perception (saññā), and perception must be clarified by mental formations.

This leads to three distortions (vipallāsa):

1. Distortion of perception (saññā-vipallāsa)

2. Distortion of thought (citta-vipallāsa)

3. Distortion of view (diṭṭhi-vipallāsa)

Don't these three distortions lead to identity-view (sakkāya-diṭṭhi)? With identity-view, whether you perform wholesome or unwholesome actions, can you escape saṃsāra? No, you cannot. This all happens because of wrong attention. Therefore, we must believe in kamma and rely on wisdom..."

You say you want happiness but perform unwholesome actions. Didn't the Buddha teach that anger is unwholesome? This already leads to suffering. Therefore, we need to avoid anger.

From the conventional truth perspective, when someone insults you, does your skin peel off? There's no need for anger. If your skin was peeling, then you should be angry. If there's no physical harm, is there any need for anger? Does it hurt like a needle prick?

In the Mangala Sutta, isn't patience declared supreme? We must examine the benefits and drawbacks. When we know there's no physical harm and no real pain, we can practice patience. Doesn't this resolve things on the conventional level?

From the ultimate truth perspective, aren't we taught to be mindful when hearing? When being mindful, is it a person or just sound? When someone calls you 'dog' or 'thief' - with mindfulness, is it a person or just sound?

Doesn't the sound itself provide evidence? Do you see a person or hear a sound? With the ear, you only experience sound. Is there any 'thief' to be found in the sound? Is there anything in the mere sound to be angry about?

Consider this: If a foreigner who doesn't understand Burmese is insulted in Burmese, would they get angry? They hear the sound, but is there anything inherently anger-provoking in the sound? If anger was inherent in the sound itself, wouldn't they become angry immediately upon hearing it?

After a year, when they understand Burmese, they might ask what 'dog's son' means. When it's explained, then they become angry. Did they get angry before understanding? This shows that anger comes from wrong attention (ayoniso manasikāra) and wrong perception.

In the form aggregate of sound, isn't it wrong perception to take it as an insult? When examined, is it an insult or just sound? The Buddha taught that hearing is covered by perception (saññā), and perception must be clarified by mental formations.

This leads to three distortions (vipallāsa):

1. Distortion of perception (saññā-vipallāsa)

2. Distortion of thought (citta-vipallāsa)

3. Distortion of view (diṭṭhi-vipallāsa)

Don't these three distortions lead to identity-view (sakkāya-diṭṭhi)? With identity-view, whether you perform wholesome or unwholesome actions, can you escape saṃsāra? No, you cannot. This all happens because of wrong attention. Therefore, we must believe in kamma and rely on wisdom..."

Yathābhūta Sukha Vibhāvanā

"What teachings should we study and rely on? People ordain as monks, build monasteries, offer kathina robes, build pagodas - all wanting happiness. When we collect all these merits, don't we say 'Idaṃ me puññaṃ āsavakkhayaṃ vahaṃ hotu' (May this merit of mine lead to the extinction of defilements)?

We need to distinguish between true and false happiness. Human happiness, deva happiness, and brahma happiness are all false happiness. Though we call them happiness, are they free from aging, sickness, and death? No, these are temporary.

These are called:

- Puññābhisaṅkhāra (meritorious formations)

- Āneñjābhisaṅkhāra (imperturbable formations)

We need to understand these saṅkhāra (formations).

In the scriptures, we find:

- Vaṭṭa-dāna (giving that leads to continued existence)

- Vaṭṭa-sīla (morality that leads to continued existence)

- Vaṭṭa-samatha (concentration that leads to continued existence)

And their opposites:

- Vivaṭṭa-dāna (giving leading to liberation)

- Vivaṭṭa-sīla (morality leading to liberation)

- Vivaṭṭa-samatha (concentration leading to liberation)

No Buddha has ever rejected dāna (giving). So what do they reject? They reject kilesa (defilements). Don't they teach about the three cycles:

- Kilesa-vaṭṭa (cycle of defilements)

- Kamma-vaṭṭa (cycle of actions)

- Vipāka-vaṭṭa (cycle of results)

Only when these three cycles cease is there Nibbāna. This is true happiness. That's why we say 'Idaṃ me puññaṃ āsavakkhayaṃ' - may these merits lead to the cessation of āsavas.

The four āsavas (mental effluents) that must end:

1. Kāmāsava (sensual desire)

2. Bhavāsava (desire for existence)

3. Diṭṭhāsava (wrong views)

4. Avijjāsava (ignorance)

To end these āsavas, one must understand:

- Khandha (aggregates)

- Āyatana (sense bases)

- Dhātu (elements)

- Sacca (noble truths)

- Paṭiccasamuppāda (dependent origination)

Only through this understanding can the āsavas be eliminated. Isn't this worth examining thoroughly?"

This teaching emphasizes the distinction between worldly happiness and true happiness (Nibbāna), and outlines the path to achieve genuine liberation through understanding fundamental Buddhist principles.

We need to distinguish between true and false happiness. Human happiness, deva happiness, and brahma happiness are all false happiness. Though we call them happiness, are they free from aging, sickness, and death? No, these are temporary.

These are called:

- Puññābhisaṅkhāra (meritorious formations)

- Āneñjābhisaṅkhāra (imperturbable formations)

We need to understand these saṅkhāra (formations).

In the scriptures, we find:

- Vaṭṭa-dāna (giving that leads to continued existence)

- Vaṭṭa-sīla (morality that leads to continued existence)

- Vaṭṭa-samatha (concentration that leads to continued existence)

And their opposites:

- Vivaṭṭa-dāna (giving leading to liberation)

- Vivaṭṭa-sīla (morality leading to liberation)

- Vivaṭṭa-samatha (concentration leading to liberation)

No Buddha has ever rejected dāna (giving). So what do they reject? They reject kilesa (defilements). Don't they teach about the three cycles:

- Kilesa-vaṭṭa (cycle of defilements)

- Kamma-vaṭṭa (cycle of actions)

- Vipāka-vaṭṭa (cycle of results)

Only when these three cycles cease is there Nibbāna. This is true happiness. That's why we say 'Idaṃ me puññaṃ āsavakkhayaṃ' - may these merits lead to the cessation of āsavas.

The four āsavas (mental effluents) that must end:

1. Kāmāsava (sensual desire)

2. Bhavāsava (desire for existence)

3. Diṭṭhāsava (wrong views)

4. Avijjāsava (ignorance)

To end these āsavas, one must understand:

- Khandha (aggregates)

- Āyatana (sense bases)

- Dhātu (elements)

- Sacca (noble truths)

- Paṭiccasamuppāda (dependent origination)

Only through this understanding can the āsavas be eliminated. Isn't this worth examining thoroughly?"

This teaching emphasizes the distinction between worldly happiness and true happiness (Nibbāna), and outlines the path to achieve genuine liberation through understanding fundamental Buddhist principles.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)