The Fracturing of the Sangha

After 200 BE (3rd century BCE), Buddhism splintered into over 18 sects, prompting Emperor Ashoka to issue edicts (found at Sarnath, Sanchi, Lauriya) forbidding monastic division (Sangha-bheda). Yet, post-Ashoka, fragmentation resumed—by the 7th century, Xuanzang noted the Sammitiyas as Mathura’s dominant school.

Archaeological Proof: The Gaughat Well Inscription

Discovered in 1863 CE (2406 BE) by Alexander Cunningham near Mathura, this Bodhisattva statue base bears a hybrid Sanskrit-Prakrit inscription:

"This Bodhisattva image was installed—along with [donor’s] parents, preceptor Dharmaka, and male/female disciples—at Shri Vihara, in honor of the Sammitiya teachers and all Buddhas."

Why This Matters:

Sectarian Stronghold: Confirms the Sammitiyas’ dominance in Mathura, a Kushan-era hub.

Social Network: Shows lay-devotee families (parents, disciples) funding art, blending domestic and monastic life.

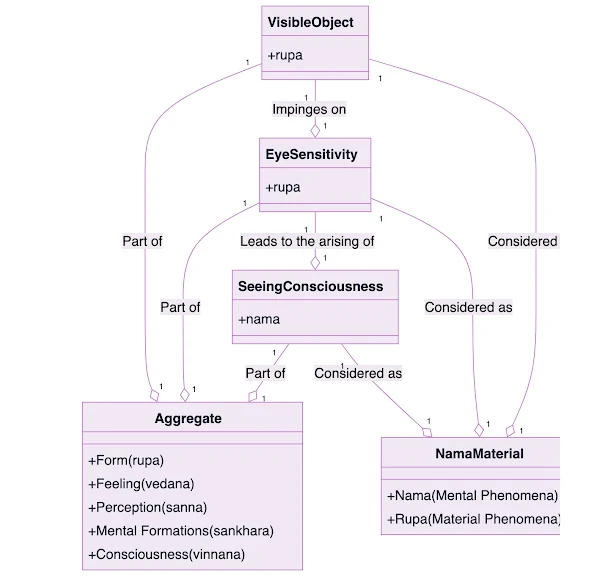

Doctrinal Clue: The Sammitiyas (Pudgalavādins) believed in a "person" (pudgala) neither identical to nor separate from the five aggregates—a controversial middle path.

Sectarian Stronghold: Confirms the Sammitiyas’ dominance in Mathura, a Kushan-era hub.

Social Network: Shows lay-devotee families (parents, disciples) funding art, blending domestic and monastic life.

Doctrinal Clue: The Sammitiyas (Pudgalavādins) believed in a "person" (pudgala) neither identical to nor separate from the five aggregates—a controversial middle path.

Xuanzang’s Corroboration

The Chinese pilgrim recorded:

Mathura had 20 Sammitiya monasteries but only 5 for other sects.

Their "Pudgala" doctrine was debated across India, yet they thrived here.

Legacy of a Lost School

Four Inscriptions: Mathura’s ruins yield three more Sammitiya-linked artifacts, now in the Mathura Museum.

Final Decline: By 1200 CE, their texts vanished—surviving only in critiques by rivals like Vasubandhu.

Four Inscriptions: Mathura’s ruins yield three more Sammitiya-linked artifacts, now in the Mathura Museum.

Final Decline: By 1200 CE, their texts vanished—surviving only in critiques by rivals like Vasubandhu.

Did You Know? The Sammitiyas were called "Vātsīputrīyas" in Sri Lanka—their name varied by region!

(Source: Cunningham’s Archaeological Survey Reports, Vol. 1)