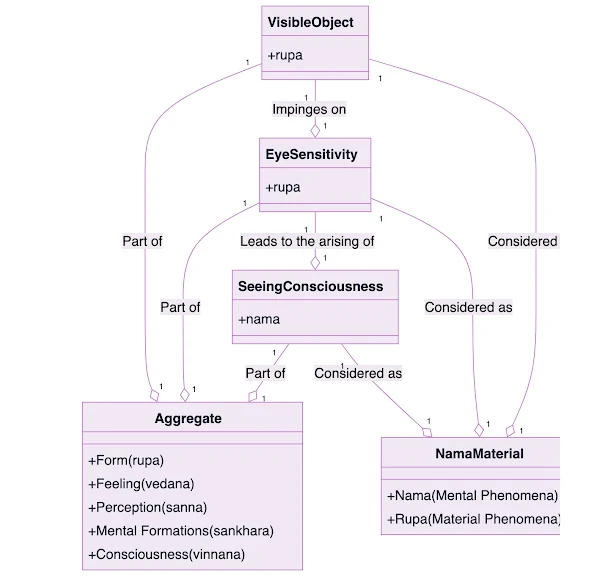

The Process (Vithi):

The Process (Vithi):1. Cakkhu-pasada (eye-sensitivity) meets visible object

2. This contact triggers cakkhu-vinnana (eye-consciousness)

3. Along with cakkhu-vinnana, three other mental factors arise:

- Vedana (feeling)

- Sanna (perception)

- Cetana (volition)

The Five Aggregates (Panca Khandha) in this process:

1. Rupakkhandha (Material aggregate):

- Eye-sensitivity

- Visible object

2-5. Namakkhandha (Mental aggregates):

- Vinnana (consciousness)

- Vedana (feeling)

- Sanna (perception)

- Sankhara (represented here by cetana)

This process illustrates important Buddhist principles:

- Dependent Origination (Paticca-samuppada)

- Non-self nature (Anatta)

- Momentariness of consciousness

In AN3.61, the Buddha explains that consciousness arises dependent on conditions, comparing it to a fire that is named according to its fuel. Similarly, eye-consciousness arises dependent on eye-sensitivity and visible objects.

The Process Components:

1. Citta (Consciousness):

- The basic awareness of the visible object

- The "knowing" element

2. Cetasika (Mental States/Factors):

- Vedana: feeling/sensation

- Sañña: perception/recognition

- Cetana: volition/intention

3. Rupa (Material Elements):

- Eye-sensitivity (cakkhu-pasada)

- Visible object

This illustrates the fundamental teaching that every moment of experience consists of:

- The knowing consciousness (citta)

- Its accompanying mental factors (cetasika)

- Physical base and object (rupa)

This analysis is crucial for:

- Understanding the non-self nature (anatta)

- Seeing dependent origination (paticca-samuppada)

- Developing insight meditation (vipassana)

As stated in the Abhidhamma, citta never arises alone but always with cetasikas. This shows the interdependent nature of mental phenomena.In the Seeing Process:

1. Rupa (Material Phenomena):

- Eye-sensitivity (physical sense base)

- Visible object

2. Nama (Mental Phenomena):

- The consciousness that knows/is aware of the visible object

This nama-rupa analysis is crucial because:

- It's simpler than the detailed citta-cetasika-rupa analysis

- It's more practical for beginning vipassana practice

- It helps break down the illusion of a solid "self"

As the Buddha taught in MN28:

"Just as when two sheaves of reeds are standing leaning against each other, so too, with nama-rupa as condition, consciousness comes to be; with consciousness as condition, nama-rupa comes to be."

In Meditation Practice:

1. First note the basic distinction:

- Physical elements (rupa)

- Knowing/experiencing element (nama)

2. Observe how:

- They arise together

- They depend on each other

- Neither exists independently

Practical Application in Meditation:

1. Mindfulness of Seeing Process:

- When practicing, note the moment of seeing

- Observe how consciousness arises with feeling, perception, and volition

- Notice these are separate phenomena, not a "self" that sees

2. Development of Insight:

- Start recognizing the difference between:

* The physical base (eye and object)

* The mental experience (consciousness and mental factors)

- See how they work together yet are distinct

3. Breaking Down the Illusion of Self:

As stated in SN22.59 (Anatta-lakkhana Sutta):

"Form, feeling, perception, formations, consciousness are not-self. If they were self, they would not lead to affliction."

Practical Steps:

1. Begin with simple awareness of seeing

2. Notice the feeling tone (vedana) that arises

3. Observe how perception (sañña) labels the object

4. Watch how volition (cetana) responds

5. See how all these factors arise and pass away

This understanding leads to:

- Direct knowledge of impermanence (anicca)

- Understanding of unsatisfactoriness (dukkha)

- Realization of non-self (anatta)Sao DhammasamiAuthor

This teaching is commonly found in:

1. Abhidhamma texts

2. Vipassana meditation manuals

3. Commentarial literature on dependent origination

If you're looking for source material on this topic, I'd recommend:

- The sections on nama-rupa in the Visuddhimagga

- Teachings on dependent origination (paticca-samuppada)

- Meditation manuals by respected teachers