Let us pay homage to the Five Infinities with joined palms, bowing with humility: Namo Buddhassa. Namo Dhammassa. Namo Sanghassa. Namo Matapitussa. Namo Acariyassa.

ဝန္ဒာမိ

Sadattheātāpino pahitattā viharatha

"Kiṃ vo, ānanda, tathāgate sarīrapūjāya? Yathābhuttaṃ, ānanda, paṭipajjatha, sadatthaṃ ghaṭatha, sadatthe appamattā hotha, sadattheātāpino pahitattā viharatha."

Announcement

Please treat any suspicious activity or messages coming from my accounts during this period with caution. I am taking immediate steps to secure my accounts and appreciate your understanding.

Pārami 30 (30 Practices of Perfection)

Question: Pārami 30 (30 Practices of Perfection)

Opening Verses

အာယန္တု ဘောန္တော ဣဓ ဒါန သီလ နိက္ခမ္မ ပညာ ဝီရိယ ခန္တီ သစ္စ အဓိဋ္ဌာန မေတ္တာ ဥပေက္ခာ ယုယ ဝေါ ဂဏှာထ အာဝုဓာနီတိ။

Āyantu bhonto idha dāna sīla nekkhamma paññā vīriya khanti sacca adhiṭṭhāna mettā upekkhā yuddhāya vo gaṇhatha āvudhānī’ti.

The Ten Perfections (Dasapāramī)

Dāna Pāramī (Perfection of Generosity)

Iti pi so Bhagavā dānapāramī-sampanno, dānupapāramī-sampanno, dānaparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Sīla Pāramī (Perfection of Morality)

Iti pi so Bhagavā sīlapāramī-sampanno, sīlupapāramī-sampanno, sīlaparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Nekkhamma Pāramī (Perfection of Renunciation)

Iti pi so Bhagavā nekkhammapāramī-sampanno, nekkhammupapāramī-sampanno, nekkhammaparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Paññā Pāramī (Perfection of Wisdom)

Iti pi so Bhagavā paññāpāramī-sampanno, paññupapāramī-sampanno, paññāparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Viriya Pāramī (Perfection of Energy)

Iti pi so Bhagavā vīriyapāramī-sampanno, vīriyupapāramī-sampanno, vīriyaparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Khanti Pāramī (Perfection of Patience)

Iti pi so Bhagavā khantipāramī-sampanno, khantupapāramī-sampanno, khantiparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Sacca Pāramī (Perfection of Truthfulness)

Iti pi so Bhagavā saccapāramī-sampanno, saccupapāramī-sampanno, saccaparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Adhiṭṭhāna Pāramī (Perfection of Determination)

Iti pi so Bhagavā adhiṭṭhānapāramī-sampanno, adhiṭṭhānupapāramī-sampanno, adhiṭṭhānaparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Mettā Pāramī (Perfection of Loving-Kindness)

Iti pi so Bhagavā mettāpāramī-sampanno, mettupapāramī-sampanno, mettāparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Upekkhā Pāramī (Perfection of Equanimity)

Iti pi so Bhagavā upekkhāpāramī-sampanno, upekkhupapāramī-sampanno, upekkhāparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Additional Perfections (Expanded List)

Dasa Pāramī (Ten Perfections Summary)

Iti pi so Bhagavā dasapāramī-sampanno, dasupapāramī-sampanno, dasaparamatthapāramī-sampanno, buddho mettā mahiddhi karuṇā muditā upekkhā pāramī-sampanno.

Thirty Perfections (Tinsapāramī)

Iti pi so Bhagavā tiṃsapāramī-sampanno.

13-17. Five Great Sacrifices (Pañca Mahāpariccāga)

- Dhana-pariccāga-dāna-pāramī (Wealth sacrifice)

- Aṅga-pariccāga-dāna-pāramī (Limb sacrifice)

- Jīvita-pariccāga-dāna-pāramī (Life sacrifice)

- Putta-pariccāga-dāna-pāramī (Child sacrifice)

- Bhariyā-pariccāga-dāna-pāramī (Spouse sacrifice)

18-20. Threefold Conduct (Tisso Cariyā)

- Buddhattha-cariyā-pāramī (For Buddhahood)

- Ñātatta-cariyā-pāramī (For relatives' welfare)

- Lokattha-cariyā-pāramī (For world welfare)

21-23. Threefold Good Conduct (Tividha Su-carita)

- Kāya-sucarita (Good bodily deeds)

- Vacī-sucarita (Good verbal deeds)

- Mano-sucarita (Good mental deeds)

All Virtues Combined

Iti pi so Bhagavā buddho anantāguṇo…

Final Closing

Iti pi so Bhagavā…

Dr. Führer and Manlae Sayardawgyi ( the story of the Horse Bone Deception)

It is believed that Dr. Alois Anton Führer deceived the venerable monk U Ma of Mandalay by claiming that a horse bone was a Buddha relic. From that incident, the venerable monk suspected something was amiss,it is revealed that the mentioned relic was enshrined at the Tawadeintha Maha Abhaya Ceti in Mandalay.

Later, the same Dr. Führer frequently requested the relic back from the venerable monk.

From the Author's Notes, Written in 2014:

The English Lord and the Relic Deception

I watched "Bones of the Buddha" by National Geographic. The author Charles Allen elaborated on the matter.

In Piprahwa, Uttar Pradesh, India, there's an ancient stupa. In 1898, an English estate owner named William Claxton Peppe excavated the stupa with laborers and discovered a large stone reliquary box. Inside were four small urns containing gold, gems, and what appeared to be flower-like decorations, about 1,600 beads, bones, and ashes. One of the urns had an inscription.

Peppe took a copy of the inscription and consulted German archaeologist Dr. Alois Anton Führer, who was then working in Nepal. Upon translating it, Führer claimed the text said: “These are the relics of the Buddha, revered along with his brothers, sisters, wives, sons, and daughters.”

W.C. Peppe then announced this find to the world. However, not long after, Dr. Führer was exposed as a fraud, accused of forging ancient artifacts and deceiving others about relics. He was dismissed from his job.

This scandal caused people to doubt the authenticity of Peppe’s relics. While the British government hesitated, the King of Thailand showed a strong interest in acquiring the relics. Eventually, the British government agreed to divide the relics: one-third stayed in England, and two-thirds were distributed.

Later, Charles Allen presented the Piprahwa urn’s inscription to Indian historian Prof. Harry Falk, who confirmed it was authentic and not forged by Dr. Führer. The stone box was dated to Emperor Ashoka’s time (~245 B.C.E). Allen concluded that the Buddha was often referred to as “the Sakya Sage” and “Sage of the Shakyas.” After the Buddha’s parinibbāna, the relics were divided and one portion was returned to Kapilavastu (Piprahwa), where Ashoka later built a stupa.

Ashoka tried to promote Buddhism as a state religion, but this faced opposition from Hindus. After Ashoka’s death, the Buddhist monuments were neglected or destroyed. The Muslim invasions later sealed this decline. The British rediscovery revived interest.

In 1971, Indian archaeologist K.S. Srivastava re-excavated the Piprahwa site and found another reliquary, suggesting that this was indeed the ancient city of Kapilavastu and that genuine Buddha relics had been rediscovered.

Charles Allen affirmed that Peppe’s discovery was authentic. However, scholar T.A. Phelps disputed this view, claiming the inscription was forged by Dr. Führer in collaboration with Peppe. Phelps highlighted that Führer had a long-standing relationship with Peppe and was involved in deceitful schemes from as early as 1896.

Official British documents reveal that Führer had tried to sell relics to the venerable monk U Ma in Mandalay, falsely claiming they were the Buddha's relics, but in fact, they were horse bones. U Ma grew suspicious and rejected the claim, noting that the relics were from a 27-foot-tall being—far greater than a horse or ordinary human.

Despite the scandal, Thailand’s Crown Prince, Jinavaravansa, who was in India at the time, expressed strong interest in the relics. The British, wary of political sensitivities, agreed to share the relics among Buddhist countries: Thailand (Wat Saket), Myanmar (Shwedagon Pagoda), Sri Lanka (Anuradhapura), and Japan (Nittaiji Temple).

However, some Indian scholars still argue that these are not Buddha’s relics but human bones. Charles Allen had the relics examined at London’s Natural History Museum, and one relic turned out to be a pig bone. He commented that this might have been mixed in during the distribution process.

K.S. Srivastava’s 1971 excavation led to a committee investigation, which concluded that some claims were exaggerated. Even Prof. Harry Falk, who analyzed the Piprahwa inscription, admitted doubts—saying even modern forgeries can look ancient.

Scientific analysis would be the best way forward. Testing rice grains from the brick structure at Piprahwa dates them between 20 AD and 220 AD, placing the construction in the early Kushan period.

Now, Peppe’s descendants plan to auction their portion of the relics. Before that, scientific analysis may confirm or refute their authenticity once and for all.

Note: There’s no confirmation that any of these relics were enshrined at Shwedagon Pagoda.

References:

-

The Bones of the Buddha: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3044472/?ref_=fn_tt_tt_2

-

Alois Anton Führer (Wikipedia): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alois_Anton_F%C3%BChrer

-

The Piprahwa Deceptions: https://web.archive.org/.../http://www.piprahwa.org.uk/

Ye Ca Buddha

(Homage to Triple Gem & Buddha's Various Relics)

ယေ စ ဗုဒ္ဓါ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စဗုဒ္ဓါ အနာဂတာ။ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ ဗုဒ္ဓါ၊သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိတေ အဟံ

ye ca buddha atītā ca, ye ca buddha anāgatā,paccupannā ca ye buddha, sabbe vandāmi te aham,

ယေ စ ဓမ္မာ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ ဓမ္မာ အနာဂတာ။ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ ဓမ္မာ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိ တေ အဟံ၊

ye ca dhamma atītā ca, ye ca dhammā anǎgatā.paccupannă ca ye dhammā, sabbe vandāmi te aham

ယေ စ သံဃာ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ သံဃာ အနာဂတာ။

ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ သံဃာ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိ တေ အဟံ။

ye ca sangha atītā ca, ye ca sangha anǎgatā paccupannā ca ye sanghā, sabbe vandāmi te aham.

ယေ စ ဓာတု အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ ဓာတု အနာဂတာ။

ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ ဓာတု၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိ တေ အဟံ။

ye ca dhātu atītā ca, ye ca dhātū anāgatā,

paccupanna ca ye dhātũ, sabbe vandāmi te aham.

ယေ စ ပါဒါ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ ပါဒါ အနာဂတာပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ ပါဒါ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိတေ အဟံ။

ye ca pādā atītă ca, ye ca pādā anǎgatā,

paccupannă ca ye pādā, sabbe vandāmi te aham.

ယေစ ဗောဓိ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ ဗောဓိ အနာဂတာ။

ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေဗာဓိ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိ ဟေ အဟံ၊

ye ca bodhi atita ca, ye ca bodhi anagata,

paccupanna ca ye bodhi, sabbe vandāmi te aham.

ယေ စ ဗိမ္မာ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ ဗိမ္မာ အနာဂတာ။

ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ ဗိမ္ဗာ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိ တေ အဟံ။

ye ca bimba atita ca, ye ca bimba anagatā

paccupanna ca ye bimbā, sabbe vandāmi te aham

ယေ စ ဒန္တာ အတီတာ စ၊ယေ စ ဒန္တာ အနာဂတာ ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေဒန္တာ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိ တေ အဟံ

ye ca dantă atîta ca, ye ca dantā anāgata

paccupannā ca ye dantă, sabbe vandāmi te ahap

ယေ စ စူဠမဏီ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ စူဠမဏီ အနာဂကာ ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ စူဠမဏ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမ တေ အဟံ။

ye ca cuļamaņi atītā ca, ye ca culamaṇī anāgata,paccupannā ca ye culamaṇī, sabbe vandāmi te aham

ယေ စ ကေသာ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ ကေသာ အနာဂတာ။ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ ကေသာ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိ တေ အဟံ

ye ca kesä atită ca, ye ca kesā anāgatā

paccupannā caye kesā, sabbe vandāmi te aham

ယေ စ မောလီ အတီတာ စ၊ ယေ စ မောလီ အနာဂတာ။

ပစ္စုပ္ပန္နာ စ ယေ မောလီ၊ သဗ္ဗေ ဝန္ဒာမိ တေ အဟံ။

ye ca moli atītā ca, ye ca moli anǎgatā,

paccupannā ca ye moli, sabbe vandāmi te aham.

ဗုဒ္ဓ-ပစ္စေကဗုဒ္ဓါနံ၊ ဓမ္မံ သံဃဉ္စ ဓာတုယော။

ဗောဓိ-စေတိယ-ဗိမ္ဗာနံ၊ အတုလယာ နမာမိဟံ။

buddhapaccekabuddhānam, dhammam sanghaññca dhātuyo,

bodhicetiyabimbānam, atulayā namāmi'ham.

Salutations to the Buddha

(Asking for forgiveness )

Okaasa-3 kaayakam, waceekam, manokam, nang-kaa, toe-hate, sop-waa,chal-kyam, nai-kam, sam yoeng cho-nan, sang-lai aw-poeng phit-kwa, punta,yein-hai, yaam-nai tamti pha-ra ratana, ta-raa ratana, sangha ratana, kiao myaet saam-poeng joe-nan, khaa maa yumko, waang-hoe kom-taw, pu-jaw,khoop-kom nom-wai, ti-khaa aww ...

nang-kaa taang-lee tee-nai, hai-lai lawt-lon pon-sei, a-pae see-poeng, kaap saam-poeng, haeng-kaat paet-poeng, khein-long haa-poeng, vipatii-ta-raa see-poeng, byassanaa-ta-raa haa-poeng, joe-nan sei-lae, hai-jiao hop-lai, jaan-ta-raa, mag-ta-raa, phol-ta-raa, nibbaan-ta-raa myaet, sei-kam ti-khaa aww...

Sadhu sadhu sadhu

Beneath the Bodhi Tree: The Final Fire Burning and the Guardian Spirits

According to my understanding and the latest data analysis, I have come to realize that the key figures who currently bear the most responsibility as Dhamma protectors—specifically in safeguarding sacred sites, guarding Buddhist temples, and watching over practitioners—are:

-

Bodhisatta Metteyya (Maitreya): The future Buddha, presently residing in Tusita heaven, who will continue to support the Dhamma even before his final birth.

-

Cātummahārājika Devas (Four Great Kings):

-

Dhataraṭṭha (Guardian of the East)

-

Virūḷhaka (Guardian of the South)

-

Virūpakkha (Guardian of the West)

-

Vessavaṇa (Kuvera) (Guardian of the North)

These deities collectively protect the sacred sites and the wider Buddhist world.

-

-

Indra (Sakka): King of the devas, who upholds righteous order and supports practitioners in times of need.

-

Hemavata:A prominent yakkha protector who once personally approached me in a diplomatic inquiry regarding a crucial voting decision about the selection of the relics custodian and their supportive care mandate.Actually He also conducted a psychological test on me to assess any potential for corruption.

Tāṇo Yakkho: (??)

-

Notable Yakkha Protectors: These beings revealed themselves to me briefly in a cave—showing their bodies only for a moment before disappearing—demonstrating their role as hidden guardians of sacred sites.

-

Notable Devas: Similar to the yakkhas, these devas appeared in a cave for only a moment, then vanished, underscoring their watchful presence.

-

One Young Man: From my understanding, he may be the one who will assume future custodianship of the relics after my own duty is fulfilled.

-

One Vijjadhora Monk: He was the one who led me to that cave and facilitated my meeting with these protective beings.

-

The Most Powerful Vijjadhora, known as The Venerable Ariya Vijjadhora Sayadaw: He is the authorized person who holds the authority to establish the “Dhātu-parinibbāna Society (Theravāda-based),” an organization dedicated to the protection and management of sacred relics.

About Dhātu-parinibbāna (The Final Extinction of Relics):

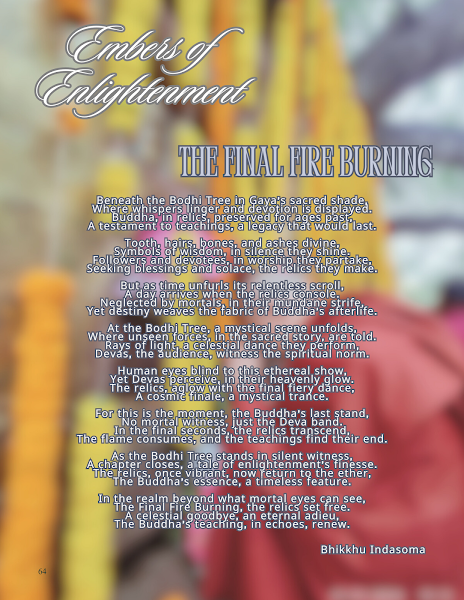

Beneath the Bodhi Tree in Gaya’s sacred shade,

Where whispers of devotion linger, the Buddha’s relics remain preserved for centuries—a timeless testament to his teachings and a legacy that endures.

These relics—teeth, hair, bones, and ashes—embody the Buddha’s wisdom. In silent radiance, they inspire generations of followers and devotees, who seek blessings and solace in their presence.

As time unfolds its relentless scroll, a prophecy reveals itself: a day will come when these relics, neglected by mortals in their mundane struggles, fulfill their final destiny.

According to the Anāgatavaṃsa tradition and related Buddhist texts, when the Buddha’s teachings (sāsana) near their end, a wondrous event will unfold at the Bodhi Tree.

On that day, unseen forces—Devas from ten thousand world systems—will gather in silent reverence. The relics will miraculously assemble from their scattered resting places—first at the Great Stupa of Anuradhapura, then at Nagadipa, and finally beneath the Bodhi Tree itself.

In this final hour, the relics will rise into the air, forming the complete body of the Buddha. Six-colored rays will illuminate the heavens, and Devas—witnesses of the spiritual realm—will pay their respects. Human eyes will not perceive this ethereal dance; only the Devas, in their celestial brilliance, will behold the final fiery dance of the relics.

This is the Final Fire Burning—the relics consumed by a self-generated flame (dhātu-parinibbāna), leaving no trace in the physical world. This marks the Buddha’s last stand, his final transcendence beyond the cycle of rebirth.

In Myanmar, inspired by these prophecies, some groups and associations and some society dedicate themselves to preparing for this extraordinary day. Some even aspire to become Vijjadhora—seekers of deep wisdom—hoping to witness the relics’ final moment and hear the Buddha’s Dhamma one last time. Others, including famous scholar monks, express their wish to become Rukkha-soe—tree guardian spirits—believing that by doing so they can witness the event from a vantage point under the Bodhi Tree and listen to the final Dhamma teaching, hoping to attain enlightenment there.

Their vision: to participate and listen to the Dhamma talk of the relics on the Final Fire Burning Day—a day awaited by countless devotees and even Devas.

According to AN 3.70, time in the Deva realms is vastly different from the human realm:

-

One day in the Catumahārājika Deva realm equals fifty human years.

-

Thirty such days make one Deva month, and twelve months make one Deva year.

-

Devas in this realm live for five hundred Deva years—equal to nine million human years.

Yet, even such long lives are ultimately impermanent. They too are subject to the cycle of death and rebirth unless they achieve liberation through Dhamma practice.

That is why these groups aspire to be reborn as Catumahārājika Devas or tree guardian spirits—not to be bound by endless cycles of birth and death, but to patiently await the final day beneath the Bodhi Tree. Until then, they dedicate themselves to preserving and protecting the Buddha’s relics, nurturing them with devotion and care.

In this way, they honor the timeless nature of the relics and the final flame that will one day set them free, leaving behind the Buddha’s teaching as an echo renewed in the hearts of all who seek the path to enlightenment.

"Note: As the author of this article, I am an ordinary young monk writing about traditional Buddhist teachings and my experence regarding custodian Devas, Yakkhas, and Vijjadharas. This writing is based on scriptural sources and traditional accounts. I make no claims of personal supernatural abilities or direct experience with these beings. This article is purely for educational purposes and sharing traditional Buddhist knowledge.

I wish to clearly state that this work does not involve any claims of jhāna, magga, or superhuman states. It is simply an academic exploration of these finding."

Sao Dhammasami

Research Scholar/Author

THE FINAL FIRE BURNINGBeneath the Bodhi Tree in Gaya's sacred shade,Where whispers linger and devotion is displayed,Buddha, in relics, preserved for ages past,A testament to teachings, a legacy that would last.

THE FINAL FIRE BURNINGBeneath the Bodhi Tree in Gaya's sacred shade,Where whispers linger and devotion is displayed,Buddha, in relics, preserved for ages past,A testament to teachings, a legacy that would last.Tooth, hairs, bones, and ashes divine,Symbols of wisdom, in silence they shine.Followers and devotees, in worship they partake,Seeking blessings and solace, the relics they make.

But as time unfurls its relentless scroll,A day arrives when the relics console.Neglected by mortals, in their mundane strife,Yet destiny weaves the fabric of Buddha's afterlife.

At the Bodhi Tree, a mystical scene unfolds,Where unseen forces, in the sacred story, are told.Rays of light, a celestial dance they perform,Devas, the audience, witness the spiritual norm.

Human eyes blind to this ethereal show,Yet Devas perceive, in their heavenly glow.The relics, aglow with the final fiery dance,A cosmic finale, a mystical trance.

For this is the moment, the Buddha's last stand,No mortal witness, just the Deva band.In the final seconds, the relics transcend,The flame consumes, and the teachings find their end.

As the Bodhi Tree stands in silent witness,A chapter closes, a tale of enlightenment's finesse.The relics, once vibrant, now return to the ether,The Buddha's essence, a timeless feature.

In the realm beyond what mortal eyes can see,The Final Fire Burning, the relics set free.A celestial goodbye, an eternal adieu,The Buddha's teaching, in echoes, renew.Bhikkhu Indasoma

References

Bodhi, B. (Trans.). (1995). The Mahāparinibbāna Sutta (DN 16). In The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Dīgha Nikāya (pp. 231–277). Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Bodhi, B. (Trans.). (1995). The Four Noble Places of Pilgrimage (Cullavagga X). In The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Saṃyutta Nikāya (pp. 1675–1680). Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

Ñāṇamoli, B., & Bodhi, B. (Trans.). (1995). The Doctrine of Impermanence (Dhammapada, vv. 277–279). In The Path of Purification (pp. 10–11). Seattle, WA: Pariyatti Publishing.

Rhys Davids, T. W., & Oldenberg, H. (Trans.). (1881). The Symbolism of the Relics (Cullavagga X). In Vinaya Texts: The Mahāvagga, Part I and II. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu. (Trans.). (1997). The Teaching of Striving Diligently (AN 4.180). Retrieved from https://www.accesstoinsight.org.

Walshe, M. (Trans.). (1987). The Rays of Light at Enlightenment (Suttanipāta, vv. 684). In The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Dīgha Nikāya. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

A Reflection on Responsibility and Consequence!

Dear respected friends and fellow practitioners,

Let me share some of my reflections on the profound link between the Buddha’s sacred relics and their custodians — a relationship that spans not only centuries but lifetimes, deeply interwoven with karma, historical developments, political challenges, and the living promise of spiritual protection.

1. Karmic Connection of Custodians

You see, the Buddha’s relics are not merely physical remains; they are profound symbols of the Dhamma itself. From the time of the Buddha’s passing, there were eight original shares of relics distributed among different groups, as recorded in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta (DN 16.5.3-4). These distributions were not without conflict — even back then, there were disputes over who should rightfully hold the relics, leading to the construction of stupas to enshrine and preserve them. This demonstrates how relics have always attracted karmic ties — drawing custodians across lifetimes to protect them, sometimes facing challenges as part of their own past karma.

2. Historical Custodial Lineage

From King Ajātasattu, who initially guarded the relics, to Emperor Ashoka, who redistributed them with the intention of spreading the Dhamma throughout his vast empire (Ashokavadana, translated by John Strong), we see a lineage of custodians who carried this karmic duty. Later, King Kanishka of the Kushan Empire also gathered and redistributed relics (as seen in Chinese Buddhist records like the A-yü-wang jing).

After the reign of His Majesty King Kanishka, Her Majesty Queen Victoria also became involved in the preservation of relics and ancient stupas. Due to her past karma, Her Majesty was drawn to these sacred duties. Even though there have been debates over whether these relics rightfully belong to India or to some regions of the old Indian subcontinent (now bearing modern city names), those arguments focus narrowly on history and geographic ties.

In reality, the true nature of these relics goes much deeper and can only be fully understood by those with a Buddhist perspective. Perhaps the British royal family members of today are not Buddhist in this life, yet it is possible that some among them were devout Buddhists in their past lives. They may have worshipped and made adhiṭṭhāna—a determined vow or resolution—towards safeguarding these relics and ensuring their protection in a future life. Hence, the relics naturally gravitate towards those with such adhiṭṭhāna, those with a deep karmic bond to them. This explains why Her Majesty Queen Victoria maintained certain ancient stupas in old India.

This is the cause and effect at work. If you doubt it, you can investigate the historical records of Queen Victoria’s orders concerning the restoration of old stupas in the Indian regions. I, too, have had dreams that revealed these connections, and I once asked England about these mysterious experiences. Now, I understand the relationship between past and present lives and the devotion that binds people to these relics. This process is unstoppable.

This lineage continues even today — with modern custodians like myself, committed to upholding both the physical preservation and the Dhamma’s integrity.

No matter how high the security, no matter how sophisticated the technology, the relics themselves move from place to place guided by their own nature. No human force can prevent this.

3. Political Dimensions

We must acknowledge that relics often attract political interest. From the earliest days of distribution, there was tension among kingdoms and groups about who should possess them — again, documented in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta (DN 16.5.3-5). It is an unfortunate reality that we, as custodians, must navigate with wisdom and compassion.

4. Spiritual Protection Aspect

According to Buddhist tradition, relics are surrounded by protective energies — a reflection of the Buddha’s own extraordinary power and his commitment to safeguarding the Dhamma. We find echoes of this idea in AN 4.191 (Paccaya Sutta), which describes the protective forces generated by righteous conduct and deep reverence. Before his final passing, the Buddha entrusted the sangha to continue his teachings and protect the Dhamma — and by extension, the relics that embody his presence.

5. A Respectful Advisory Regarding the Sacred Relics and Their Custodians

While I acknowledge that from time to time there are international (external) affairs where matters related to the Buddhist Sasana—such as conferences, assemblies, or official meetings—are discussed, including decisions about heritage preservation, I feel compelled to address a deeply important issue regarding the Buddha’s sacred relics and their custodians.

According to the ancient Buddhist traditions, these sacred relics are not merely archaeological or historical objects but are deeply enshrined in the spiritual fabric of the universe. They are under the protection and guardianship of many divine beings, who fulfill their roles with utmost responsibility and commitment:

6. The Four Great Kings (Cātummahārājika Devas):

-

Dhataraṭṭha — Guardian of the East, protector of the Dhamma’s spread in that direction.

-

Virūḷhaka — Guardian of the South, upholder of the monastic order’s stability.

-

Virūpakkha — Guardian of the West, custodian of the Dhamma’s transmission across regions.

-

Vessavaṇa (Kuvera) — Guardian of the North, overseer of the wealth of wisdom and the protection of relics.

7. Lokapālas (World Protectors):

-

Indra (Sakka) — King of the Devas, ensures the balance of righteousness and supports the Dhamma.

-

Yama — Oversees karmic justice and moral discipline.

-

Varuṇa — Associated with order and cosmic law.

-

Kubera (also Vessavaṇa) — Supports the stability and guardianship of relics and shrines.

8. Notable Yakkha Protectors:

-

Āḷavaka, Sātāgira, Hemavata, Punnaka, Suciloma, Khara — each with specific responsibilities to guard the relics, prevent desecration, and ensure rightful veneration.

9. Nāga Kings as Custodians:

-

Mucalinda, Nandopananda, Erakapatta, Apalāla — protectors of relics in water bodies, underground chambers, and ancient stupas.

10. Temple Guardian Deities:

-

Vajrapāṇi — enforcer of spiritual protection.

-

Jambhala — protector of prosperity and spiritual resources.

-

Mahākāla — guardian of time and protector against desecration.

11. Dhamma Protectors:

-

Uppalavanna, Sumana (Sri Pada), Kataragama deviyo — supporting the safeguarding of the Buddha’s teachings and relics.

12. Local Area Guardians:

-

Rukkha devas (tree spirits), Bhummā devas (earth spirits), Ākāsa devas (sky spirits) — custodians of specific relic sites.

13. Specific Site Guardians:

-

Saman (Sri Pada), Vibhīsana (Sri Lanka), Ganesh (at some temples) — protectors tied to sacred sites across different regions.

Each of these beings, across realms and traditions, holds a solemn duty to safeguard the relics, prevent desecration, and uphold the dignity and sanctity of these symbols of the Buddha’s enlightenment and teachings.

14. Important Reminder

Yet, I must also remind — with the utmost respect — that those who seek to harm, delay, deny, or misuse these relics, especially with political or authoritarian force, should be mindful of the karmic consequences of such actions. As the guardians of these sacred treasures, we have a duty — rooted in the Buddha’s own instructions — to ensure that any attempt to defile, exploit, or obstruct their preservation will meet with the appropriate response.

This is not a threat, but a solemn reminder of cause and effect — kamma vipāka — that even the Buddha himself emphasized throughout his teachings.

15. Declaration of Custodianship and Protection of the Buddha’s Relics

As the custodian of the sacred relics of the Buddha, I stand in unwavering commitment to uphold and protect the sanctity of these relics from any form of violation or desecration.

With deep reverence and in the name of the Buddha, I hereby declare that any act of wrongdoing, harm, or violation against these sacred relics shall be subject to the rightful and immediate intervention of the deva—the celestial custodians of the relics—who hold the responsibility and power to act without delay.

I solemnly charge all custodians—Yakkhas, devas, and all beings who have sworn to protect these relics in accordance with the Buddha’s teachings—to remain ever-vigilant and to fulfill their promises without hesitation or delay.

May this declaration stand as a reminder of our collective duty, rooted in the Dhamma, to honor, safeguard, and venerate these relics, ensuring their sanctity endures for the benefit of all sentient beings.

May the Buddha’s blessings guide and protect all who carry out this noble duty.

A Humble Appeal to All:

From my own direct experience and deep understanding, I respectfully advise all readers to avoid any attempt to subject these relics to testing, analysis, or any form of disturbance without my concerns and approval(as i am the one of the custodian). Such actions may disrupt the spiritual balance maintained by these guardians and could lead to unforeseen consequences that may not be immediately apparent.

A Final Word:

Let us remember that relics are not just physical remnants; they embody the Dhamma, and their protection is entrusted to both the seen and the unseen—monks, nuns, lay devotees, and divine guardians alike. Therefore, I ask you to treat them with the utmost reverence, avoiding any wrong action that may compromise their sacredness or bring about karmic repercussions.

May all beings act wisely and with compassion.

Peace-Building Role

As a researcher in Peace Studies and Buddhist Studies, I humbly accept the responsibility to remind all of us that the Buddha’s message is one of peace and non-violence. As he taught in the Dhammapada (verse 5):

“Hatred never ends through hatred. By non-hate alone does it end. This is an ancient truth.”

The relics themselves are powerful reminders of this truth — living symbols of the Buddha’s teachings that call us to embody peace and compassion in our actions.

Dear friends, let us together honor the relics, cherish their symbolism, and protect their sanctity — not for power or prestige, but as an expression of our shared commitment to peace, compassion, and the Dhamma’s living flame.

May the Buddha’s teachings continue to illuminate our hearts, guide our actions, and inspire us to build a more peaceful world.

"Note: As the author of this article, I am an ordinary young monk writing about traditional Buddhist teachings regarding custodian Devas, Yakkhas, and Vijjadharas. This writing is based on scriptural sources and traditional accounts. I make no claims of personal supernatural abilities or direct experience with these beings. This article is purely for educational purposes and sharing traditional Buddhist knowledge.

I wish to clearly state that this work does not involve any claims of jhāna, magga, or superhuman states. It is simply an academic exploration of these findings."

Sadhu! Sadhu! Sadhu!

Sao Dhammasami

Siridantamahāpālaka

The Nature of the Buddha’s Relics: Then and Now

As a custodian of the Buddha’s relics, I find myself reflecting on the Buddha’s own struggles during his lifetime and how they mirror the challenges I face today in preserving these sacred objects.

Even before his final days, the Buddha encountered many hardships, both internally and externally. In his very first Dhamma talk—the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (SN 56.11)—he faced resistance from his own close disciples, the five ascetics, who were initially reluctant to listen to him. Despite their hesitation, he persevered, guiding them gently toward understanding.

The Buddha’s path was never easy. He faced opposition from within his own followers and from external religious institutions. According to the Anguttara Nikaya (AN 3.66), there were even three attempts on his life—a sobering reminder that not everyone welcomed the light of the Dhamma.

His solitary struggles are also well-documented. The Dhaniya Sutta (Sn 1.2) beautifully describes the Buddha’s contentment in solitude, even amid challenges. Yet, there were moments of profound loneliness. For instance, when Venerable Meghiya left him alone during a critical time (AN 9.3), the Buddha remained silent and composed, reflecting his deep equanimity.

In the Dīgha Nikāya (DN 16), we read of the incident at the Capala shrine, where the Buddha felt a strong desire for water but struggled to find clean drinking water—an experience that echoes the challenges faced by seekers of truth who, even today, may struggle to find pure resources amid defilements and obstacles.

Internal Sangha disputes were not uncommon. The Kosambiya Sutta (MN 48) recounts how the Buddha’s own disciples divided into factions over disagreements about Vinaya rules. In the Kinti Sutta (MN 103) and the Sāmagāma Sutta (MN 104), the Buddha had to guide his followers through disputes and help them maintain harmony.

These references remind me that the challenges I face today—political pressures, false claims, misunderstandings, and betrayals—are not new. The Buddha himself faced them, and he taught us how to respond with patience, wisdom, and unwavering dedication to the Dhamma.

One passage that resonates deeply with me is from AN 5.77:

“These are the five future dangers, as yet unarisen, that will arise in the future. Be alert to them and, being alert, work to get rid of them.”

The Buddha’s teachings and relics have always needed protection—from ignorance, from greed, from doubt. Today, as I work to preserve his relics and share their significance with the world, I draw strength from the Buddha’s own struggles and victories.

May this work continue to honor his legacy, despite the challenges that remain. May those who walk this path find courage in his example and wisdom in his words.

With respect and determination,

Bhikkhu Indasoma Siridantamahāpālaka (Sao Dhammasami)

Research Scholar, Buddhist Studies

Hswagata Buddha Tooth Relics Preservation Museum

"Note: As the author of this article, I am an ordinary young monk writing about traditional Buddhist teachings regarding custodian Devas, Yakkhas, and Vijjadharas. This writing is based on scriptural sources and traditional accounts. I make no claims of personal supernatural abilities or direct experience with these beings. This article is purely for educational purposes and sharing traditional Buddhist knowledge.

I wish to clearly state that this work does not involve any claims of jhāna, magga, or superhuman states. It is simply an academic exploration of these finding."